Rafaqat Ali*, Amar Nasir, Sadaqat Ali, Benish Ali and Muhammad Kamran Ameen

College of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Jhang Pakistan

Corresponding author*: rafi.ali99@yahoo.com

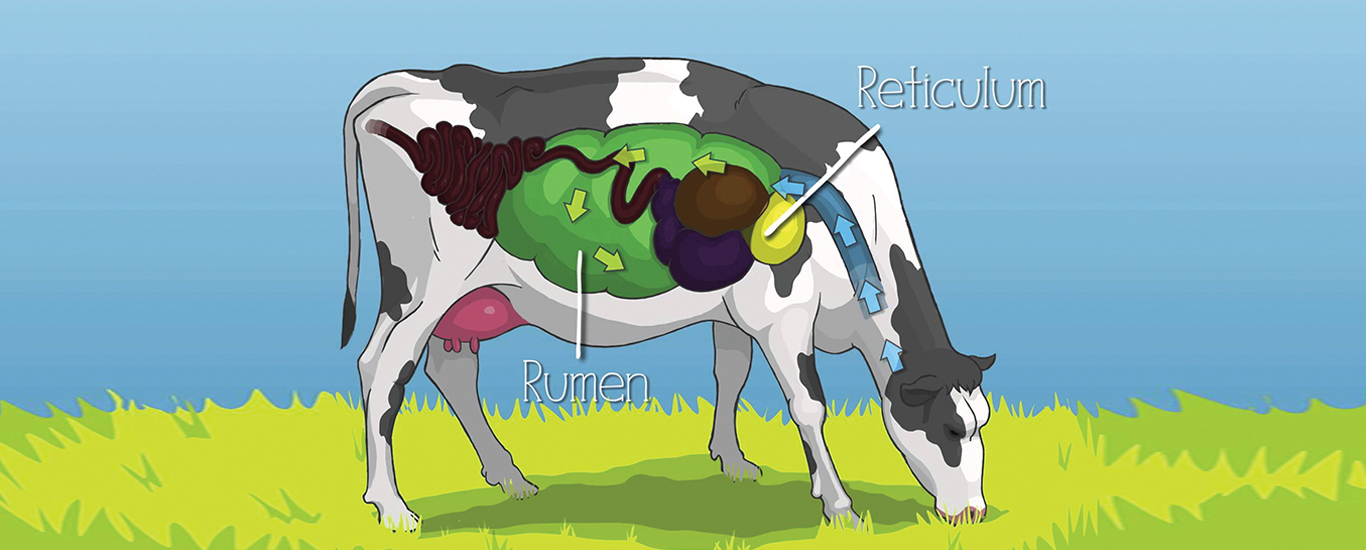

Bloat is an over distention of the rumenoreticulum with the gases of fermentation, either in the form of a persistent foam mixed with the ruminal contents–called primary or frothy bloat, or in the form of free gas separated from the ingesta–called secondary or free-gas bloat. It is predominantly a disorder of cattle but may also occur in sheep. The susceptibility of individual cattle to bloat varies and is genetically determined.

In primary ruminal tympany, or frothy bloat, the cause is entrapment of the normal gases of fermentation in a stable foam. Several factors, both animal and plant, influence the formation of a stable foam. Bloat is most common in animals grazing legume or legume-dominant pastures, particularly alfalfa, ladino, and red and white clovers, but also occurs with grazing of young green cereal crops, rape, kale, turnips, and legume vegetable crops. Legume forages such as alfalfa and clover have a higher percentage of protein and are digested more quickly. Other legumes, such as sainfoin and birdsfoot trefoil, are high in protein but do not causes bloat, probably because they contain condensed tannins, which precipitate protein and are digested more slowly than alfalfa or clover. Leguminous bloat is most common when cattle are placed on lush pastures, particularly those dominated by rapidly growing leguminous plants, but can also occur when high-quality hay is fed.

In seconday ruminal tympany, or free-gas bloat, physical obstruction of eructation occurs from esophageal obstruction caused by a foreign body, stenosis, or pressure from enlargement outside the esophagus (as from lymphadenopathy). Interference with esophageal groove function in vagal indigestion and diaphragmatic hernia may cause chronic ruminal tympany. This also occurs in tetanus. Tumors and other lesions of the esophageal groove or the reticular wall are less common causes of obstructive bloat. There also may be interference with the nerve pathways involved in the eructation reflex. Lesions of the wall of the reticulum (which contains tension receptors and receptors that discriminate between gas, foam, and liquid) may interrupt the normal reflex that is essential for escape of gas from the rumen.

Unusual postures, particularly lateral recumbency, are commonly associated with secondary tympany. Ruminants may die of bloat if they become accidentally cast in dorsal recumbency or other restrictive positions in handling facilities, crowded transportation vehicles, or irrigation ditches.

Bloat is a common cause of sudden death. Cattle not observed closely, such as pastured and feedlot cattle and dry dairy cattle, usually are found dead. In lactating dairy cattle, which are observed regularly, bloat commonly begins within 1 hr after being turned onto a bloat-producing pasture. Bloat may occur on the first day after being placed on the pasture but more commonly occurs on the second or third day.

Rumen motility does not decrease until bloat is severe. If the tympany continues to worsen, the animal will collapse and die. Death may occur within 1 hr after grazing began but is more common ~3-4 hr after onset of clinical signs. In a group of affected cattle, there are usually several with clinical bloat and some with mild to moderate abdominal distention. Death rates as high as 20% are recorded in cattle grazing bloat-prone pasture, and in pastoral areas the annual mortality from bloat in dairy cows may approach 1%. There is also economic loss from depressed milk production in nonfatal cases and from suboptimal use of bloat-prone pastures. Bloat can be a significant cause of mortality in feedlot cattle.

Congestion and hemorrhage of the lymph nodes of the head and neck, epicardium, and upper respiratory tract are marked. The lungs are compressed, and intrabronchial hemorrhage may be present. The cervical esophagus is congested and hemorrhagic, but the thoracic portion of the esophagus is pale and blanched–the demarcation known as the “bloat line” of the esophagus. The rumen is distended, but the contents usually are much less frothy than before death. The liver is pale due to expulsion of blood from the organ. Usually, the clinical diagnosis of frothy bloat is obvious. The causes of secondary bloat must be ascertained by clinical examination to determine the cause of the failure of eructation.

In life-threatening cases, an emergency rumenotomy may be necessary; it is accompanied by an explosive release of ruminal contents and, thus, marked relief for the cow. Recovery is usually uneventful with only occasional minor complications.

A trocar and cannula may be used for emergency relief, although the standard-sized instrument is not large enough to allow the viscous, stable foam in peracute cases to escape quickly enough. A larger bore instrument (1 in. [2.5 cm] in diameter) is necessary, but an incision through the skin must be made before it can be inserted through the muscle layers and into the rumen. Picture If the cannula fails to reduce the bloat and the animal’s life is threatened, an emergency rumenotomy should be performed. If the cannula provides some relief, the antifoaming agent of choice can be administered through the cannula, which can remain in place until the animal has returned to normal, usually within several hours.

When the animal’s life is not immediately threatened, passing a stomach tube of the

largest bore possible is recommended. A variety of antifoaming agents are effective, including vegetable oils (eg, peanut, corn, soybean) and mineral oils (paraffins), at doses of 80-250 mL. Dioctyl sodium sulfosuccinate, a surfactant, is commonly incorporated into one of the above oils and sold as proprietary antibloat remedies, which are effective if administered early.

Management practices that have been used include feeding hay before turning cattle on pasture, maintaining grass dominance in the sward, or using strip grazing to restrict intake. For hay to be effective, it must be at least one-third of the diet. Feeding hay or strip grazing may be reliable when the pasture is only moderately dangerous, but these methods are less reliable when the pasture is in the prebloom stage and the bloat potential is high. Mature pastures are less likely to cause bloat than immature or rapidly growing pastures.

The only satisfactory method available to prevent pasture bloating is strategic administration of an antifoaming agent. This is widely practiced in grassland countries such as Australia and New Zealand. The most reliable method is drenching twice daily (eg, at milking times) with an antifoaming agent. Available antifoaming agents include oils and fats and synthetic nonionic surfactants. Oils and fats are given at 2-4 oz (60-120 mL)/head/day; doses up to 8 oz (240 mL) are indicated during most dangerous periods. Poloxalene, a synthetic polymer, is a highly effective nonionic surfactant given at 10-20 g/head/day and up to 40 g in high-risk situations. It is safe and economical to use and is administered daily through the susceptible period by adding to water, feed grain mixtures, or molasses. Alcohol ethoxylate detergents are equally effective and are more palatable than poloxalene. Ionophores are effective in preventing bloat, and a sustained-release capsule that is administered into the rumen and releases 300 mg of monensin daily for a 100-day period protects against pasture bloat and improves milk production on bloat-prone pastures.

The ultimate aim in control is development of a pasture that permits high production, yet results in a low incidence of bloat. To prevent feedlot bloat, feedlot rations should contain at least 10-15% cut or chopped roughage mixed into the complete feed. Preferably, the roughage should be a cereal, grain straw, grass hay, or equivalent. Grains should be rolled or cracked, not finely ground. Pelleted rations made from finely ground grain should be avoided. The addition of tallow (3-5% of the total ration) may be successful occasionally, but it was not effective in controlled trials. The nonionic surfactants, such as poloxalene, have been ineffective in preventing feedlot bloat, but the ionophore lasalocid is effective in control.