Muhammad Farooq

Elko Organization (Pvt.) Ltd.

Mastitis in dairy cattle is a major problem that causes massive economic losses on most dairy farms. The direct and indirect economic losses of mastitis to farmers are numerous: milk yields are reduced, milk that is contaminated, treatment costs, higher culling rates and even occasional fatalities. The whole dairy and milk processing industry incurs losses because of problems that result from SSC in milk, and the reduced quality of milk. Mastitis cannot be eradicated but can be reduced to low levels by good management of dairy cattle – buffaloes and cows. The inflammation of the udder is common in dairy herds causing significant economic losses to the dairy farming business.

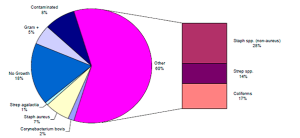

Although the main causes of infectious mastitis are bacteria, however fungi, yeasts and possibly virus can also cause udder inflammation.  Nevertheless, among several causes of mastitis only those associated with microbial infection is important to take into consideration. The most commonly occurring pathogens are Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus. dysgalactiae, Streptococcus. uberis and Escherichia coli that mainly cause herd outbreaks. When the teats of cows are exposed to these pathogens and they penetrate the teat duct and establish an infection in one or more quarters within the udder of the cattle.

Nevertheless, among several causes of mastitis only those associated with microbial infection is important to take into consideration. The most commonly occurring pathogens are Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus. dysgalactiae, Streptococcus. uberis and Escherichia coli that mainly cause herd outbreaks. When the teats of cows are exposed to these pathogens and they penetrate the teat duct and establish an infection in one or more quarters within the udder of the cattle.

All dairy cattle are continuously exposed to pathogens that can cause mastitis. The number of pathogens in the milk varies: from less than a thousand to several millions per ml of milk but it is usually less than 10,000 per ml and further diluted by the milk from the majority of uninfected quarters. The exposure of cattle teats to Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus agalactiae and Streptococcus dysgalactiae greatly increases when teat sores and lesions on teat-ducts are colonized by these mastitis pathogens and when the animal lie on contaminated bedding.

Dairy cattle can develop a very large pathogen population within a few days due to optimum conditions, like moisture and temperature. Bedding becomes moist and contaminated with faeces and with sufficient warmth the growth of Escherichia coli and Streptococcus uberis is rapid that causes frequent outbreaks of mastitis.

Commonly pathogens penetrate during milking, in the intervals between milking and sometimes when cows are not lactating. Even when very small numbers of pathogens penetrate the duct infection usually occurs.

The duration of the infection varies generally; from a week or so to several months in a mild form which is not easily detected by the farmers. In case of some pathogens like E coli, the infection is frequently more acute associated with general endotoxaemia, presence in the blood of endotoxins, with raised body temperature, appetite loss and even death of the dairy cattle if supportive therapy is provided in time.

The duration of the infection varies generally; from a week or so to several months in a mild form which is not easily detected by the farmers. In case of some pathogens like E coli, the infection is frequently more acute associated with general endotoxaemia, presence in the blood of endotoxins, with raised body temperature, appetite loss and even death of the dairy cattle if supportive therapy is provided in time.

In the event of infectious mastitis the effective therapy is a course of antibiotic infusions through the teat duct to eliminate the bacterial infection. In most cases infections may spontaneously recover but most persist to be eliminated eventually by antibiotic therapy or when the cattle are culled. However, the susceptibility of cows varies considerably and new infections are most common in older cows in early lactation, at the start of the dry period and during poor herd management.

Three main patterns of infectious mastitis are observed in cattles: The most common among them is caused by Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus aureus and Streptococcus dysgalactiae. These are subclinical infections and if the rate of new infection is considerably reduced the proportion of infected quarters will decline slowly over the period of several years. General good management includes clean milking methods, teat disinfection by dipping or spraying to prevent infections by reducing exposure to pathogens.

The other type of infections occurs frequently in housed cattle. These are typified by acute clinical mastitis during early lactation. The main pathogens that cause these infections are Streptococcus uberis and Escherichia coliform. The epidemiology is such a way that these are not controlled by teat disinfection although drying off is useful in preventing some infections like Streptococcus uberis that commonly occur early in the  dry period but it will not reduce the Streptococcus uberis and Escherichia coliform infections occurring at, and soon after, calving.

dry period but it will not reduce the Streptococcus uberis and Escherichia coliform infections occurring at, and soon after, calving.

The third type and most typical of infection occurs in non-lactating cows and buffaloes commonly in early part of the dry period particularly with Streptococcus uberis and most persist causing clinical mastitis in the following lactation.

It is important to recognize that because most mastitis is subclinical and unseen control depends primarily on adopting sound management routines for the whole herd. It cannot be achieved by using laboratory tests to identify individual infected cows and taking special action with these animals. Tests are useful to alert farmers to the extent of the problem but they rarely indicate steps additional to those that should be in the daily routine.

Some simple routine will reduce the proportion of infected cows and clinical mastitis by at least 70% if used regularly at each milking. Mastitis caused by Streptococcus agalactiae will be reduced to very low levels and is frequently eradicated. To reduce the proportion of infected cows and clinical mastitis farmers should adopt good herd management practices as proper feeding, housing and hygiene to reduce exposure to pathogens.

Some simple routine will reduce the proportion of infected cows and clinical mastitis by at least 70% if used regularly at each milking. Mastitis caused by Streptococcus agalactiae will be reduced to very low levels and is frequently eradicated. To reduce the proportion of infected cows and clinical mastitis farmers should adopt good herd management practices as proper feeding, housing and hygiene to reduce exposure to pathogens.

All equipment used should be cleaned thoroughly when milking; preferably bedding materials should be changed daily and cattle should not be housed under dirty conditions. Dirty udders should be washed with clean running water thoroughly and dried with disinfected cloth. After milking, teats should be dipped with appropriate disinfectant to avoid the occurrences teal lesions, sores and chaps.

Teat injury or fly attack can be prevented by using teat duct, hence reducing the chances of pathogens’ penetration. “Detecting clinical mastitis by examining foremilk can reduce the duration of infections. By avoiding low lying grazing land and damp areas where flies are common will also reduce mastitis in non-lactating growing cattle or cows in the dry period. Also it is helpful to move cattle from areas known to give problems with mastitis.”

Dairy cattle should be treated with antibiotics recommended only by veterinarian. All animals should be treated, specially alternatively treat those that have previously shown signs of infection because the reduction in infection is sometimes not immediate but levels fall in one year and continue to fall in successive years.