By Muhammad Hamza, Ahmad Raza Fareed, Zil-e-Huma, Saif Ullah, Faisal Rehman, Shumaila Kousar, Ayesha Arif, Ambreen Noor, University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences Lahore, Sub campus Jhang

Crimean-Congo Hemorrhagic Fever (CCHF) is a viral illness caused by the Nairovirus, belonging to the Orthonairovirus genus in the Bunyaviridae family. The virus was initially identified in the Crimean region of Russia in 1944 and later confirmed to be identical to the Congo virus found in the Congo basin in 1967.

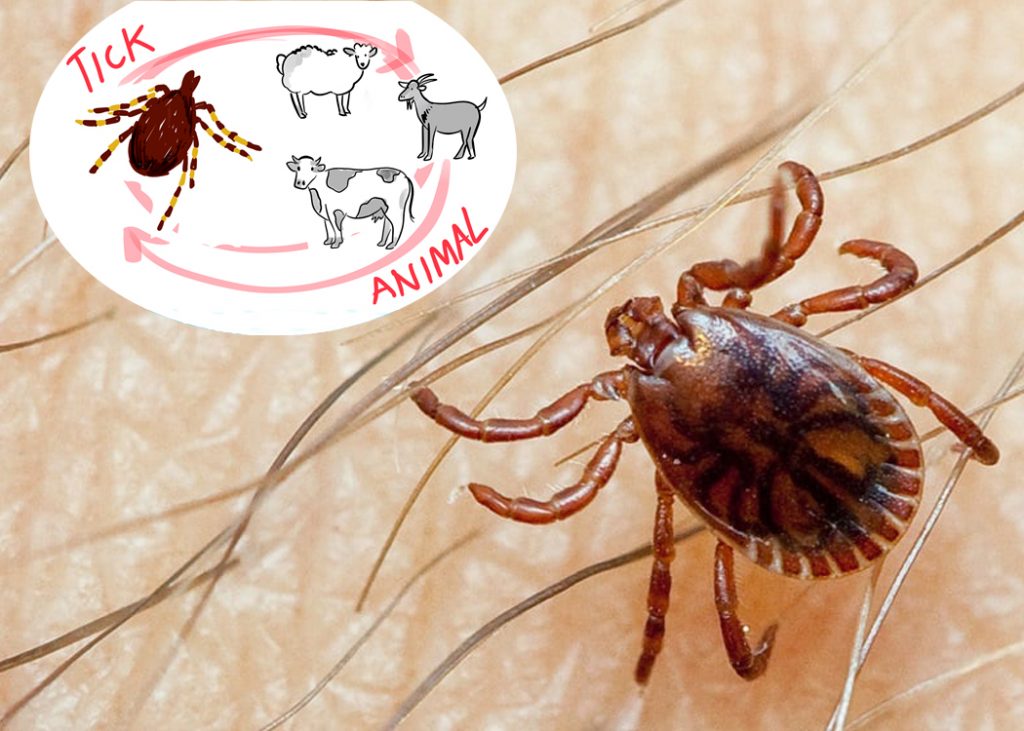

It is a severe zoonotic disease, prevalent in Africa, the Balkans, the Middle East, and Asian countries below the 50th parallel north. The primary tick vector for CCHF is of the Hyalomma genus, and both wild and domestic animals, including cattle, sheep, and goats, serve as hosts. Ostriches, though resistant, can contribute to human cases, as seen in a South African outbreak.

CCHF spreads through tick bites, contact with infected animal blood or tissues during slaughter, and, in animals, through transovarial transmission. Factors such as climate change, increased tick numbers, and improved viral detection contribute to its high transmission rates.

Most cases involve individuals in the livestock industry, such as agricultural workers, slaughterhouse employees, and veterinarians. Human-to-human transmission occurs through close contact with infected bodily fluids or hospital-acquired infections.

The risk of tick-to-human transmission can be curbed by wear protective clothing (long sleeves, long trousers), wearing light colored clothing for easy detection of ticks on the clothes, using approved

acaricides (chemicals intended to kill ticks) on clothing, and approved repellent on the skin and clothing, regularly examining clothing and skin for ticks. If found ticks should be removed safely. Visits to the areas where ticks are abundant should be avoided, especially in the seasons of their hyper activation.

The incubation period varies based on virus acquisition mode, with symptoms including sudden fever, myalgia, dizziness, and gastrointestinal issues. Mortality rates range from 10% to 40%, with death typically occurring in the second week of illness.

In animals, clinical signs are mild, and diagnosis involves methods like ELISA, antigen detection, serum neutralization, RT-PCR, and virus isolation. The antiviral drug ribavirin has shown some efficacy in treating CCHF.

CCHF prevention or control in animals is hard to ensure as the tick-animal-tick cycle usually goes unnoticed and the infection in domestic animals is mostly discrete. Furthermore, the tick vectors are numerous and widespread, so use of acaricides (chemicals intended to kill ticks) is the only realistic option in livestock production facilities.

After an CCHF infection outbreak at an ostrich abattoir in South Africa, the handlers ensured that ostriches remained tick free for 14 days in a quarantine station before slaughter. This decreased the

animal infection risk during slaughtering and prevented human transmission to humans who were in contact with the livestock.

The risk in humans can be reduced by raising awareness, educating on risk factors, and adopting preventive measures. The risk of animal-to-human transmission can be reduced by wearing gloves and other protective clothing while handling animals or their tissues in endemic areas, notably during slaughtering, butchering, and culling procedures in slaughterhouses or at home. Animals should be quarantined before they enter slaughterhouses or routinely treated with pesticides two weeks prior to slaughter.

To reduce the risk of human-to-human transmission in the community, close physical contact with CCHF-infected people should be avoided, besides wearing gloves and use of protective equipment when taking care of sick people. Hands should also be washed regularly after caring for or visiting patients.

While a vaccine for humans is not widely available, reducing the risk of transmission involves protective clothing, acaricides, and repellents for tick prevention, and precautions during animal handling.